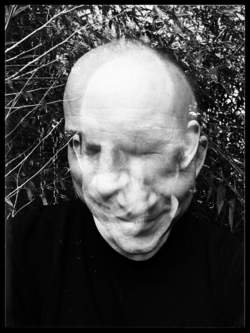

J.ROBBINS

'When someone has a song and they’re struggling about - what’s the best way to present it...'

06/07/2020, Danil VOLOHOV

Looking at the creativity of J.Robbins, we can say that he’s probably a rare example of a musician who has practically tried everything. His recent solo-debut titled Un-Becoming will be a proof of this. Prior to that, Robbins used to work as producer and engineer on dozens of records.

His career started in the late 80’s, and transformed over the years – firstly, with Jawbox. Then with Burning Airlines, Office For Future Plans and Channels.

Unlike most producers, J. Robbins found, with his methodology and approaches, the balance between being a songwriter, releasing his own material and being a producer. Just like 20 years ago – Robbins is still full of ideas and ready to explore very different paths.

In the interview for Peek-a-Boo Magazine, J.Robbins told us about the hardcore scene and Government Issue, about Jawbox and the production aspect of his work, about becoming a producer and “Un-Becoming”, about songwriting and the place of music in his life.

I guess I may call you one of those highly-productive artists who release a record every two to three years, perhaps even more often. But after all these years and releases, do you consider songwriting to be a certain need you feel like the basic human needs: the need for food or the need for communication?

Definetely! Definetely! Although, I don’t think that I’m that prolific in real-time. And as life goes on, I have a tendency to think I’m not really prolific. But in times when I felt I couldn’t or shouldn’t be making music – I discovered that I can’t stay sane without doing it. So better to say – it keeps me sane ( laughs ). So I really do feel it’s something I have to do. Even if it’s not songwriting, some kind of musical activity has to be happening for me – for sure.

A few years prior to the release of your debut solo-album you were more focused on acoustic work. With “Un-Becoming”, you combined different sound palettes in such songs as “Radical Love”, instrumental passages – “Kintsugi”. And such highly dynamic tracks as “Solder On” or “Our Own Devices”. What were your initial goals on this record ?

This is gonna sound silly but my goals were just to write songs. Every project I’ve done before now has always been a band-type-of-collaboration. Even if I could point to specific songs and say: “Ok, I pretty much wrote this song, or that song”- there’s always been a point in which the collaborative part would kick in. And the band would always finish things all together. And sometimes that’s extremely rewarding. Like in the band Channels, which I do with my wife. Channels is a totally collaborative band. And in Jawbox, sometimes I’d bring parts and we’d jam. And that would drive us away from where I initially expected to go. Or we would just start jamming and sort of come up with stuff altogether. I may be the person who would dictate the final flow of it, just because we’d arrange the final version around whatever the lyrics and vocals would do; that can be really rewarding and amazing. But sometimes for me in the past, I’ve felt I was using the band-format as a bit of a crutch. Like, I’d just have some material and would not really know where I want it to go. So I’d let the band kind of figure it out altogether. Well, I didn’t wanna do that anymore. I really wanted to be as coherent as possible, and know what I was trying to say - to take responsibility, take ownership of what’s said. Even so, there are some collaborative elements still, because there are other musicians. I’m playing with them specifically because of their voices and what they’d bring to it.

I started playing acoustic shows around 2010. And I started getting really into the idea of a strong song being one you can play in any kind of format. For example, for Jawbox songs a lot of them wouldn’t make any sense to play just with acoustic guitar and vocals, because they’re so rhythmically based. And the identity of the songs has so much to do with all the pieces meshing. It’s not any individual thing that makes it work; it’s the collective that makes it work. What I started getting into more recently is just the idea that the song should be portable. A song is more about what you’re singing. And the kind of bones of it – for it to be a really good song for me you really have to be able to take that with you. You don’t need to have those individual mechanical pieces all fitting. The essence of the song has to be strong if it’s played by just one person on an acoustic guitar. So those are the kind of songs I wanted to try writing …And that was probably the motivation behind the album. It’s not 100% that way, because there are things on there that I can’t play solo acoustic. But at least I feel like I’m responsible for the content. I’m not leaning on anybody else’s inspiration to get it through. It’s 100% percent my inspiration. That’s important for me in the way of proving something to myself. I’m a really big fan of John Cale, and this is a thing I really notice about his music. He put out this acoustic live-record called “Fragments Of A Rainy Season” … But he’s put out a bunch of live-records. Every time he goes to play his songs, he does it with different group of people, and each time it will have a different flavor. Maybe the arrangement would be really wildly different. But the essence of the song is always still there. And that’s the thing I really wanted. I thought: “That’s the essence of songwriting – you have this definite point of view, you’re expressing it, you’re communicating from the essence of who you are to the person listening to it. It’s very direct! And all the other things around it – arrangements etc., could be anything! But the essence of the song has to still be there. So that was what I really wanted to do.

Even though now you’re living in Baltimore your name is mostly associated with the musical scene of D.C. Government Issue became the point of entry for your career. After hardcore-punk established itself within such bands as Minor Threat or Scream how it did it feel for you to become a part of GI and the hardcore movement ?

It was huge for me! Joining Government Issue completely changed my life! I was going to shows … and not just hardcore shows - there was a lot of really good weird underground music in D.C. in the 1980’s. For me, I was really shy kid. And when I was a teenager, before I got into punk-rock, a lot of what I’d do is just sit in my house and play piano. I had a lot of passion about music and art. But I didn’t know how that would translate into the real world. I kind of didn’t know where I was gonna go, or what I supposed to be doing. I was living in my own little world. And the punk-rock scene in D.C. was the first place where I saw people just putting their creativity out into the world and not giving a damn. It was really-really energizing. It was like opening a door. And made me feel like I had permission to create things and I could be a part of something. Nobody was telling these people that they had to have this qualification or that qualification. Or that they needed permission. They just were doing it. That was hugely influential to me. And when I tried out for Government Issue – I didn’t think I would get in. I barely knew how to play bass. To this day I didn’t know why they accepted me. It was one of my favorite bands. I tried out. I was really nervous. It was almost like… it wasn’t like a joke. But I was just laughing: “There’s no way for me to actually get into this band!”. And then I did! It really changed my whole life. Everything happened in my life has flowed out of that, really.

After GI broke and your formed Jawbox – was it hard for you to change your musical accents ? As obviously, even in the context of “Grippe”, we can say that this is a band with different musical accents and energies.

Yeah! Starting Jawbox was like starting from scratch. In Government Issue, that was a pretty collaborative band. But in the end, the songs were really determined by the guitar-player and the singer. I wrote a lot of bass-parts for Government Issue, and we wrote a lot of songs that came out of the bass-parts. But as far as turning them into songs –that was really Tom’s [note. – Tom Lyle, the guitarist of Government Issue] job in the band. I started feeling like I wanted to direct how things would go. I wanted to play guitar. I thought it would be easier to hear the whole song; if you’d bring a song to the band and you’re the bass-player, you have to do a lot of extra work to explain to everybody what you’re hearing in your head. While if you’re bringing the song on guitar, it’s easier for people to hear the shape of it. Maybe. That’s what I thought, anyway. And I wanted to sing – I love singing. John [Stabb] had a very specific style, and there were so many other ways to approach singing. So I really just wanted to widen the palette of what kind of songs I could create for people. But I also was 19-20 years old. So to me, early Jawbox sounds like anybody’s first band. When you got your favorite record, you listen to it and you’re like: “Oh! Really love The Lemonheads!” – so you try to write like The Lemonheads songs. Or “Oh, I really love Big Black!” – so you try to write a Big Black song. It’s a melting pot of influences from your record collection. The early days of Jawbox were pretty much like that to me. And then, over time, the lineup changed little bit. And then we all started to trust our own inner voices more, listening more to what we actually had going on… I mean, we always did, we always were influenced by our record collections and new things we heard, we always were borrowing things but it wasn’t quite as brazen as our early stuff. That how that sounds to me, anyway.

It was a cool time. It was a little bit like anything goes. I never liked hardcore scenes that were really codified, where it had to be really hard and really fast. Really “from the streets,” all that bullshit. The exciting part of it was the permission to create. And not have the rules about what you could and couldn’t do.

As guitarist you've never been afraid of putting a maximal tension to your guitar-parts and to explore different paths. And this is the thing you’ve been doing until now. But how much did your approach change, after all these years, projects and experiences ?

I hope I always have an open mind about how to create things! That’s my goal anyway – is not calcify. But I think, overall it’s just an ongoing process of learning to trust myself more. I feel like the best ideas come when you’re not trying so hard. You kind of tune-in into something and let it happen. I really think that’s definitely true. My best things I’ve done, the things I’m proudest of were not ideas that came because I was consciously trying to do this or that thing. They came because I was just playing and singing and being receptive to a moment. So I think that process is a lifelong process: learning to be in the moment, listen and trust your creativity trying to get into a flow of things. I don’t want to sound like a total hippie. But I think that’s what that is for me.

I can’t but notice that within Burning Airlines, your songwriting changed quite a bit. You got deeper within your approach to the lyrics – it became much more poetical and much more expressive. What affected these changes ?

Well, I super appreciate…It really blows me away that you know my stuff ( laughs )! And that you’re listening to it so closely! It’s quite wonderful to me! Thank you for that! But I think part of it to me is the same trip of learning to trust oneself. For example if Jawbox – especially with the lyrics…I mean, everyone in the band wrote lyrics. A lot of the lyrics are jammed together from everyone’s contributions. But a lot of the lyrics I wrote – specifically at that time, I was almost terrified to be understood. It was a combination of liking the process itself, and jamming together images and phrases that feel good to sing. Or images that seem interesting. I’d sometimes just jam them together in the context of a vocal melody. And I wouldn’t really know what the song is supposed to be about until I was half-way done writing it. At that point I could attach it to something that I was trying to work out personally - something within me. But then I was scared to be understood! So I was trying to make sure that it remained obscure. Some of those lyrics turned out good and interesting, but a lot of them are just a sort of mess to me.

In Burning Airlines, the lyrics were not collaborative. They were all mine. Apart from the songs that Bill [Barbot] sings. And I worked much harder on making sure that they were about things. Even if they were about obscure things. Like we had a song based on this TV show called “The Singing Detective” – it was a Dennis Potter show. It was a really crazy show, about a guy who was dying in a hospital with psoriatic arthritis. So his skin was basically falling off because of this autoimmune condition. So he’s in agony all the time, and he hallucinates about being a detective trying to solve a crime. What those hallucination and dreams are really about is, he’s going back to some source of terrible guilt and pain from earlier on his life. It’s on this metaphorical level. The show is really amazing. He keeps drifting into dream states. So sometimes he’s in the hospital. And it’s the real world. But he’s actually dreaming and all the doctors and nurses are doing musical numbers. Sometimes he dreams back into this kind of 1940’s hardboiled film-noire-detective scenes…It’s a crazy show. It’s really great. That’s a pretty obscure source for a song. But I felt like it really resonated with me. And became an inspiration for the Burning Airlines’ song - “Morricone Dancehall”. So I think there’s more of an attempt to be about specific things. Songs about the town I grew up in, a lot about relationships and stuff … they were personal. But I tried to be more clear about their meaning than I would have done in Jawbox.

With all these projects you took a part in – Burning Airlines, Office For Future Plans, Channels – do you consider them being different stages of your career, or it’s more like your continuation to explore different musical tendencies ?

I hope it’s different! The answer is both, I guess. I hope it’s different. I hope I’m not doing the same thing over and over again. But to the degree I am, I hope it’s getting better and better ( laughs ).

It is really!

Thank you ( laughs )! And a lot of times, with all these bands – there’s always the thing about the people you’re playing with too. Channels, I think, was the really amazing growth moment for me, because I was making music with my wife who’s really truly my life-partner. And with Darren Zentek who’s been a really great friend of mine for a long time. But also a really big inspiration to me. And the process we had in that band - which we still have; we don’t play hardly at all, but we say we’re not broken up, we could get together and make more Channels music anytime - the thing particularly about playing with Darren is that he was a big teacher for me as far as trusting a moment, getting into a jam and just listening to each other. And letting something develop without talking about it or trying to dictate it. That was a huge step forward to me – playing with Darren. Every time I play with different people – I think it’s true for everybody, right ? When you try to make music with different collaborators it has to be learning experience. It’s one of the great values you can get from it.

When you work on something – not necessarily as musician, but as producer as well, what helps you to define the components you should add to it in order to reach the destination ?

I think it’s different in every circumstance. I think, the most important thing you can do if you’re trying to help somebody make a document of their art is to listen to them. Try and hear the essence of what it is. Try to understand what it is they’re trying to achieve. And keep one eye on what you can do to heighten the elements that are already there. As opposed to being… some peoples’ idea of a producer is someone who remixes what you’re doing, or kind of brings so much of their own essence to it. And that can be really great; I’ve had enjoyable experiences like that, but more as musician then as producer. Going back to that idea of collaboration what I tend to think of – myself, if I produce a record, or if I’m an engineer or whatever it is, I’m there to serve the interests of the artists and art they’re trying to make. So…being receptive and maybe you know them well enough and there’s mutual trust so if someone’s going in a counterproductive direction they can trust me to say: “No, wait a minute, let’s not do it that way, here are other ways that might work here better.” In the end I see it as: I work for them, they don’t work for me.

You have a reputation of producer who puts a stress on pre-production work. It’s quite productive in terms of your interpersonal approach – it allows you to maximize work on arrangements that kind of stuff. But is it always a productive way of working for you ?

More often than not – I think it’s really important. But I wish I had more chance to do pre-production with people. More recently, I mean. People just don’t have enough time and budgets to do as much pre-production. I haven’t had a chance to do much of it lately. And there are also times when it wouldn’t make sense. Like there are bands where the very best thing you can do is let them just come in and play their material. And just try to capture it faithfully. And I really love that kind of recording. But even so, there’s a degree of pre-production to that. Because it’s better to know it ahead of time. It’s better to be familiar with the band and the material. To be able to say: “No! We don’t have to get together and go over the thing because all you have to do is to come in and execute it! Just get psyched and make it happen!” But it just depends. It’s just one of the things that make it so interesting for me – there are so many different kinds of roads you can take. Sometimes it’s actually really vital, and that’s what the artist wants and what’s called for, when someone has a song and they’re struggling about what’s the best way to present it. And what’s the best arrangement they could have. That can be really great, the process of going though material and trying to make sure that it’s as strong as it could be. And it’s cool ‘cause it can be different every time. It’s not one size fits all. But yeah, I’d say that’s really important. Just like in anything, to be prepared. Even if the preparation is the matter of knowing that everything’s fine, and just go ahead and doing it.

By the time you started recording “For Your Own Special Sweetheart” you were well-rehearsed. But having the music written you didn’t have the songs written. Don’t you think that this fact brought a certain spontaneous element to this music and this recording ?

Yeah. I think in certain circumstances it can be great! A little bit of spontaneity can actually render really exciting results. But it just depends on the circumstances. Some people are really excellent at that way. And some people are not ( laughs ).

You’ve always been speaking about your work with Ted Niceley as a great learning process. What lessons did you learn from Ted at that point ?

Oh…I learned some very basic and crucial things from Ted. They all had to do with listening. Like a certain way of listening and focus…There was a lot of stuff about my own musicianship. And ways of listening to performances. That was really a lot of what I leant from Ted. Because we had the luxury of having a lot of time to work on the record we made with him. I had never focused on the mechanics of my guitar-playing in that way. Or the mechanics of band-ensemble. I knew if we were speeding up too much, or slowing down. But I never noticed that I’d grip the guitar in a certain way so that very often, even if the guitar was in tune, I was playing out of tune. I never really understood about being ahead or behind the beat until we recorded with Ted. And so much we did with Ted involved listening to that kind of thing. So it was really like going to school. It was not great for my confidence as a singer. But that’s an ongoing thing too. Because it was very hard work doing vocals for that record. And I didn’t feel quite prepared enough. I didn’t feel like anybody trusted me to execute my ideas very well. And the more I tried to do it – I was digging a big hole. Ted had incredible patience with me which was great. So that was another thing that I’ve learnt. It was just to cultivate patience. But a lot of it was just being able to put a microscope on aspects of performance. And understand how to improve things I was doing and that were kind of detrimental. It was really-really crucial.

Mostly, you started working as producer by the time you finished your work on “Sweetheart”. At that point you used to record such artists as Kerosene 454 and Texas Is the Reason. How did you start doing it ?

Really, a lot of it was…Maybe people in these bands were fans of Jawbox. And I knew them enough…In case with Kerosene 454 – they had just moved to Washington D.C. and they were looking for a place to record. And I was really in love with the studio where we’d done “For Your Own Special Sweetheart” and the engineer we’d worked with. And I thought: “What if we’d do it up here ?” and they said: “Come along with us!”

So it was a combination of being friends with people and also having some respect for my band, knowing that I had kind of been though this boot camp of recording which was recording “For Your Own Special Sweetheart”. I think that’s the main thing that started it off…

As producer, what are the things you usually put your stress on and what are the consistent components of your methodology ?

I think, those things in terms of mechanics like being in tune and on time. But here’s the funny thing too: when we did “For Your Own Special Sweetheart” with Ted Niceley – I learned so much about this kind of mechanical aspect – the nuts and bolts aspects of performances. And kind of looking at the big picture very pragmatically. But the next record Jawbox made, we made it with John Agnello, who’s a completely different kind of producer. And I’d say that his great strength was to put us at ease and generate the feeling of confidence. We were very intense about the quality of our performance – all those mechanical things we’d learnt while working with Ted. We were really intense about being in tune and on time. And making sure that the tempo was right. But John’s focus was much more about the feeling of things, and he was able to really create a feeling that we’re gonna do excellent work no matter what, that he was our ally, and it was all gonna be great. Those are the two sides of the coin to me…those guys are both big mentors to me. Like you have to get the details right, which is something I definitely got from Ted. But also that the studio is a place where people feel vulnerable, and it’s important to find the way to help them know that everything’s gonna be cool. That they’re powerful, and they’re gonna do something amazing. Making a record, making any kind of art, making any kind of document like that is an amazing process. I’m still in love with the process. It’s a beautiful thing. And it’s wonderful to see people make their dreams become manifest. Realizing the potential they have in their heads. Trying to cultivate all those things is an important part to me. Otherwise the process is great because there’s a bazillion ways you can make a record. It’s just whatever suits the moment. The nuts and bolts methodology of it is nowhere near as important as being confident about content and feeling good execution.

Within some of your worksprojects you contribute to the process not only as a person working on production and engineering. But also, as musician involved in the process. For example you played drums at Marigold’ record – “Audible To Animals” – such kind of contribution. Is there any strict distinction between these roles – producerengineerco-writer or with every project you’re trying to be maximally involved ?

No. It’s just whatever is required. If I’m invited to contribute in whatever way then I’m just excited to contribute. There are definitely times when it’s very clear to me that’s I’m just employed as engineer. And just try to facilitate without making any kind of creative contribution. And that’s fine. But there are other times, which can be really fun, where I have much more broad invitation to participate. That’s really great too. But to me it’s just about getting the artists to the place they want to be – creatively. It’s great and really rewarding for me if someone thinks I have a musical contribution to make beyond just kind of coaching, being en engineer and kind of spotting them on the balance beam. It’s sort of all-part-of-the-same-thing. It’s distinct from being full-on-collaborator with the project like Camorra, which I did with Zach Barocas and Jonah Matranga, where we all just get in studio together and came up with stuff. That was fully collaborative. In the end, I mixed that record[note. – “Mourning, Resistance, Celebration” ], but I mixed it as a band-member. That’s a totally distinct kind of thing.

There been a couple of records I can think of where I ended up playing bass on the record but I really had no artistic stake in the music. I was just there because somebody needs to play bass - and that’s fine too. Or someone needs a harmony and I can hear the harmony, and we’re short of time, so rather than fishing around for something, I might just do it. If they like it – it stays. If they don’t like it – then we do something different.

Speaking about Jawbox reunion, you noticed that it was a quite different experience. Mainly, due to the festival shows. Last summer you played your first tour over nearly 20 years – “The Impartial Overview”. How did it feel and in what way was it different ?

That’s huge question ( laughs )! It felt really good. I think the essence of the answer has a lot to do with difference between 25 years old and being 52 years old. I think it was nice for all of us. It was kind of goal for all of us to revisit the band that took up so much of our energy in our 20’s. And your 20’s can be such time…Speaking personally, I was pretty freaked out in my 20’s. I was kind of flailing around trying to figure out what I was going to do in my life, in my relationships and just living. The benefit of much more experience and the fact that we all are still friends made it possible to come back to the band in a more grounded and confident way. And really be a better team. Really appreciate the value of what it was we were able to do. The fact that anybody cares about it, especially after all this time, was really meaningful for us. It was always meaningful for us back then. But I think in perspective it gave us a chance to appreciate it more, being at an age where you hopefully realize the real value of good things you’re accomplished. And for us, I think it was all the way positive. Just to come back together…And there’s so much we did being a band. We were very conscious about what we were doing. We managed our band business very consciously, and worked very hard on our music and everything about it. But at that time and that age things can go past you and you’re not able to grasp on to them in the way you maybe can later on in life…I don’t know! But it was wonderful experience. That tour was super fun on all levels. I don’t know what future necessarily holds for us cause we had plans for 2020 that are now…

Is there something coming out soon ?

There’s nothing of mine. Because, I have mostly been writing. Or trying to write. It’s pretty hard to focus on it in the same way right now because of all the things are going on [note. - around the pandemic]. So I don’t have anything prepared. My wife Janet has a project called “Greetings From Data Lake” which is an electronic project, and she’s about to put out a song next week. We’ll probably collaborate on some things. She did some collaboration with Chad Clark of Beauty Pill. And so that’s pretty exciting.

Danil VOLOHOV

06/07/2020

Next interviews

THE HERESY GENE • 'The More We Do It, The More Important It Feels.'

PIGS PIGS PIGS PIGS PIGS PIGS PIGS • 'We probably came a little bit more confident in ourselves'

NZ • Attitude And Passion

JACKY MEURISSE (SIGNAL AOUT '42) • 'After the improvisation, I went into experimentation...'

AMBER TEASER • We Also Like Putting Some Strange Elements In Pop Music

EMPUSAE • One thing is for sure... I'll never stop making music!

PREEMPTIVE STRIKE 0.1 • ‘I Love The Belgian Scene’

DYLAN WITTROCK • 'Sometimes I just write characters’ thoughts, like journal entries.'

JOE BOYD • Producer of Pink Floyd, Nick Drake, Nico, R.E.M, talks about the years of experience and his coming book.

JOSH KLINGHOFFER (PLURALONE,RHCP) • “I suddenly found the piano the most exciting instrument to write on.”